Taken on December 24, 1968, “Earthrise,” was to become one of the most influential photographs ever taken. It would evoke emotions, provoke environmental awareness, and help define an era. The photograph was originally composed with a vertical moon surface, but we’ll get to that.

Forty-two years ago, Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, Jr. and William A. Anders, in Apollo 8, became the first astronauts to exit Earth’s orbit, and circle the moon 10 times over the next 20 hours.

The mission included high resolution image capture. The Apollo 8 Press Kit explains, “Photography seldom before has played as important a role in a spaceflight mission as on Apollo 8. A large quantity of film of various types has been loaded aboard the Apollo 8 spacecraft for lunar surface photography and for items of interest that crop up in the course of the mission. Camera equipment carried on Apollo 8 consists of two 70mm Hasselblad still cameras with two 80mm focal length lenses, a 250mm telephoto lens, and associated equipment. For motion pictures, a 16mm Maurer camera with variable frame rates will be used. Lunar Stereo Strip Photography (will be done with) overlapping stereo 70mm frames shot along the lunar orbit.

“Apollo 8 film stowage is as follows: 3 magazines of Panatomic-X intermediate speed black and white for total 600 frames; 2 magazines SO-368 (ASA 64) Ektachrome color reversal for total 352 frames; 1 magazine SO-121 Ektachrome special daylight color reversal for total 160 frames; and 1 magazine 2485 high-speed black and white (ASA 6,000, push to 16,000) for dim-light photography, total 120 frames. Motion picture film: 9 130-foot magazines SO-368 for total 1170 feet, and 2 magazines SO-168 high speed interior color for total 260 feet.” Hardly a frame to spare.

NASA’s Apollo Flight Journal shows that shooting an Earthrise was just as frenetic as our ever-popular earthbound sunset and moonrise shots today. Many crews call it “monkeytime:” that brief, perfect moment between the daylight and dark, usually punctuated by a frenzy of lens changes, light readings, exposure adjustments, film loading, mag changes or digital menu navigating. Little has changed. Read this edited NASA transcript on the “making of Earthrise:”

Borman: Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!

Anders: Hey, don’t take that, it’s not scheduled. (Chuckle).

Remember, they only have enough film for 600 black & white or 160 color shots. Commander Borman takes a picture of Earthwise with magazine E, loaded with black and white film.

Borman: (Laughing) You got a color film, Jim?

Anders: Hand me that roll of color quick, will you…hurry. Quick.

Lovell : It’s down here?

Anders : Just grab me a color. That color exterior…Hurry up!

Borman : Got one?

Anders : Yeah, I’m looking for one.

Lovell : C-368.

C-368 refers to film type SO-368, Ektachrome ASA 64 color transparency film. Lovell has found magazine B whose images will eventually get the prefix “AS08-14.”

Anders : Anything, quick…well, I think we missed it.

Lovell : Hey, I got it right here!

Anders : Let…let me get it out this window. It’s a lot clearer.

Borman : Well, take several of them.

Lovell : Take several of them! Here, give it to me.

Anders : Wait a minute, let’s get the right setting, here now; just calm down.

Borman : Calm down, Lovell.

Lovell : Well, I got it right…Oh, that’s a beautiful shot. 250 at f/11.

With the magazine of color film and 250 mm lens, Anders proceeds to photograph the two iconic shots of the earthrise.

Lovell : Now vary the exposure a little bit.

Anders : I did. I took two of them.

Lovell : You sure we got it now?

Anders : Yes, we’ll get…we’ll…It’ll come up again, I think.

Lovell : Just take another one, Bill.

Bill Anders photographed the Earth coming into view alongside the moon’s surface. He framed the shot the way he faced, with the moon’s surface vertical, on the right. It wasn’t until later that photo editors back on earth would rotate the Hasselblad’s square format 90° clockwise and reproduce NASA’s royalty-free Photo AS08-14-2383, to become one of the most famous images in history.

A year and a half later, the July 1969 Apollo 11 moonwalk was simultaneously recorded onto magnetic tape by three NASA stations. The direct recordings were not broadcast quality, so they set up regular TV cameras pointed at the small black-and-white TV screens in the observatories. In the years after, NASA reused these archive tapes and erased them to record other missions. About 250,000 tapes from the Apollo era, including many tapes of the moonwalk, are likely lost forever. Luckily for posterity and for The Whole Earth Catalog, the iconic Apollo 8 Earthrise photo was shot on film and couldn’t be erased.

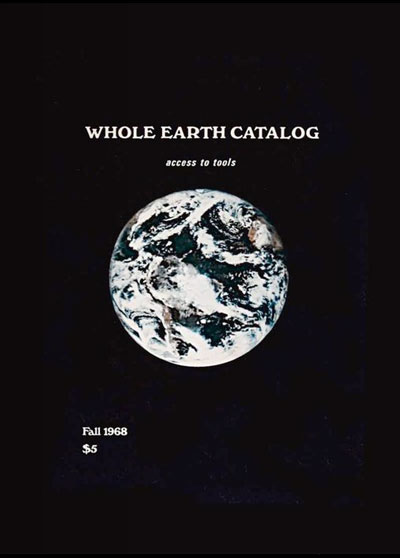

The first Whole Earth Catalog came out in 1968. Like this issue of Film and Digital Times, it didn’t sell anything. It was a resource, like an early Google: tools and where to find them.

Stewart Brand, the editor, wrote in his introduction, “The Whole Earth Catalog functions as an evaluation and access device. With it, the user should know better what is worth getting and where and how to do the getting.” About the NASA images on the cover, “They gave the sense that Earth’s an island, surrounded by a lot of inhospitable space.” Not coincidentally, the first Earth Day was celebrated in 1970. It was a pivotal moment. People suddenly realized that our planet was a fragile place, handle with care.

Fast forward to 2007. Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency launched Kaguya (SELENE), a lunar orbiter that included an HD video camera developed by NHK. At IBC 2010, one of the hits of the show was NHK’s new 8K video camera and the spectacularly life-like images it could produce.

Which brings us to December 2010 and this Whole Film and Digital Times Catalog of Cool Tools. Our cover says “Converging Worlds.” Although convergence and 3D certainly has everyone’s attention, this is the historic year of convergence and collision between consumer and professional equipment. New cameras for high-end production were previously introduced at a leisurely pace of one or two a decade. Now, an annual outing to NAB or IBC is no longer sufficient; equipment is introduced at a startling rate with each season, and our pages swell.

This December 2010 issue is a window on where we are in the technique and technology of motion picture production. Soon, more people may be “capturing” than viewing images.

The Whole Earth still looks like a fragile place. As Thomas Friedman recently wrote, 2010 was Earth’s hottest year on record. 98 out of 100 scientists will tell us that our continued carbon emissions pose enormous risk. 2 out 100 scientists say it doesn’t. A betting person would bet on the 98 who worry about climate change. Are we feeling lucky?

Where do we go from here? In 2011, I think we’ll see the unleashing of 4K. Anamorphic wide screen will lure us back into theaters. PL mounted lenses will continue to be the standard for high-end productions. Film will continue to be the standard against which everything else is compared in 2011. Happy Holidays and may all your images be beautiful in the New Year.

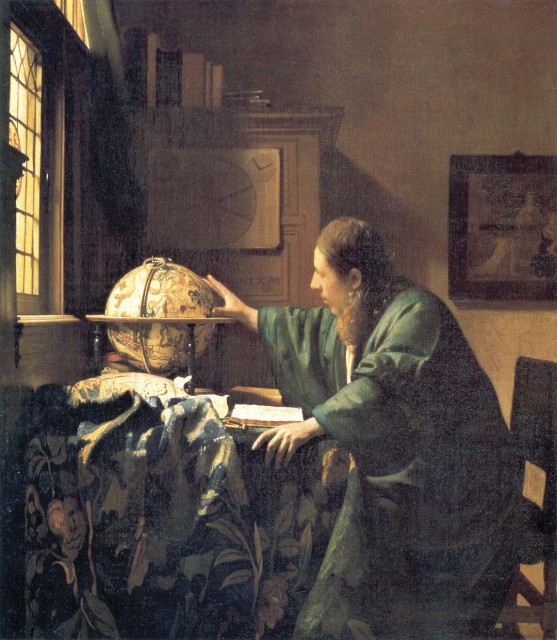

Three hundred years before Earth became a brand name on Brand’s Whole Earth covers, Johannes Vermeer focused our single-source attention on The Astronomer, with perspective lines conveniently converging on his celestial globe. It was an excellent year for astronomy. Isaac Newton completed the first successful reflecting telescope (using mirrors instead of lenses). In 1668, astronomy was an excellent profession; celestial navigation was essential to the Netherland’s thriving economy based on global trade. Which is why the Astronomer’s green robe is significant.

Christiane Hertel explains, in Seven Vermeers, the Japonsche Rok was a kimono tailored into a kind of house robe. The kimonos were given to Dutch merchants on their annual visit to the Imperial court in Edo (Tokyo), the only time they were permitted on the Japanese mainland. The remainder of the year, the merchants were required to live on the island of Deshima. The Dutch empire was at its height, with spices, silks, teak, coffee, and tea being shipped from its colonies around the world.

Remember Shogun? The year is 1600. John Blackthorne, English navigator on a Dutch trading ship, is shipwrecked on the coast of Japan. He becomes an ally of Toranaga, falls in love with his interpreter, and is assimilated into Japanese culture.

Banjin, by Andrew Laszlo, ASC (the distinguished cinematographer and author) continues a couple of centuries later, 1843. Another shipwreck. A Japanese boy, Masahiro, is rescued by American whalers and brought to New Bedford, Massachusetts. The boy is well educated at Exeter, advises Congress, goes back to sea, joins the Gold Rush in California, and returns home to Japan. He becomes a political advisor, and helps open Japan to the west as a leading character in the Meiji Restoration.

Our worlds continue to shrink, along with the size of our cameras, while their sensors become larger, the number of users multiplies, as, hopefully, does the appreciation of gorgeous Vermeer lighting.